Contents

- House Terminology

- Architectural Periods & Styles

- First Period: 1625–1725

- Georgian: 1725–1780

- Federal: 1780–1830

- Greek Revival: 1830–1860

- Gothic Revival (1840–1880)

- Italianate (1850–1885)

- Second Empire (1860–1880)

- Stick (1860–1890)

- Queen Anne (1880–1910)

- Shingle (1880–1900)

- Colonial Revival (1880–1955)

- Tudor Revival (1910–1940)

- Prairie (1900–20)

- Craftsman (1905–1930)

- International, Modernistic, Modern and Neoeclectic (1920–Present)

House Terminology

Many of us struggle to name the myriad structural and decorative components that make up a house. This section introduces basic architectural terms and focuses on the larger shapes and elements that help distinguish one house form from another.

Basic House Shapes

With few exceptions, all houses are composed of boxes with roofs. The shape of the box and the shape and orientation of the roof define a house’s characteristic form. The simplest house form is a single box with a gabled roof. A gable, the wall that encloses the end of a roof, can occur at the side or the front of the box.

The earliest house forms in America were side-gabled (Figure A). The familiar New England saltbox style is a variation of the side-gabled form in which a lean-to addition continues the back roof slope (Figure B). A new house form was introduced in the early 19th century with the front-gabled (also called end-gabled) houses of the Greek Revival and continued into the Victorian period (Figure C). Cross gables occur when roof gables intersect at right angles (Figure D).

Figure A. This side-gabled house has single central chimney.

Figure B. Side elevation of a saltbox house.

Figure C. The porch of this front-gabled house has a pediment over the entrance stairs.

Figure D. Cross-gables.

Roof Variations

A gambrel roof is gabled with two slopes on each side of a center ridge – a shallow slope above a steeply pitched slope; it is also known as a Dutch roof (E). In a hipped roof, which has no gables, four sloping surfaces form the roof (Figure F). Mansard (also called French) is a hipped roof variation with two slopes, in which the lower slope is steeper than the upper slope (Figure G).

Figure E. This side-gabled house has a gambrel roof with three dormers.

Figure F. This house, perfectly square-shaped and known as a Four Square, has a hipped roof.

Figure G. The mansard roof of this carriage house is topped by a cupola.

Projections

Projections from the basic box shape take various forms. A wing is a relatively large side projection that is smaller than the main mass. An ell is an addition that creates an L-shaped floor plan; it is usually added to the rear of a building. Smaller projecting elements include porches, porticos (Figure H), enclosed entries, dormers (Figure E), cupolas (Figure G) and towers.

Figure H. This portico is supported by columns and surmounted by a pediment.

A pediment (Figure G) is the triangular space forming the gable end of a building, or the same form used elsewhere in architecture and decoration. Pediments, which are often seen over doors and entries, can be straight, curved or broken (notched at the top, as in Figure I).

Figure I. The pediment over this door is broken.

Any one of a building’s faces can be called a façade, but the term is generally used for the main face that contains the principal entrance. Elevation refers to a scaled architectural drawing of the front, rear, or side of a building.

Windows

Windows provide important clues to the age and style of a house. Glass was a rare and expensive commodity until the 17th century in America, and most early window openings were covered with fabric, skins, paper, or solid wood sashes. When glass became more common, it was used in small square or diamond-shaped panes (also called lights) held in place by wooden or metal frames. As glassmaking technology improved and prices fell through the 18th and 19th centuries, windowpanes grew in size. By the mid 1900s, panes large enough to fill a single sash became available. The most common window types were casement (side hinged, single sash) or single- or double-hung with upper and lower sash.

Eighteenth century windows generally featured 12 or more panes per sash. A window with 12 panes in both the top and bottom sash is described as “12 over 12.” In the early 19th century, nine- and six-pane sash became more common. By the mid-19th century, a single sash could contain four, three, two, or even a single pane of glass. The molding elements separating individual panes of glass in a sash are called muntins or mullions (Figure A).

Figure A. A single-hung 6 over 9 window on a Georgian period house.

The horizontal element forming the base of a window (or door) is called the sill (Figure A). Its counterpart at the top of the window is the lintel (Figure A). Window openings may feature decorative surrounds of projecting molding and incorporate Classical elements, described later in this section. Grouped windows are termed paired, ribbon (three or more uniform windows in a horizontal band), or Palladian. Palladian windows feature a central arched window flanked by two rectangular windows (Figure B). A bay window is a projection from the outer wall of a building that creates a recess, or bay, within (Figure C).

Figure B. This Palladian window appears on a Federal style house on Main Street.

Figure C. Two-story tower bay on a Shingle Style house.

Doors

The earliest doors seen in American houses were board and batten, made of vertical planks held together by battens. They were replaced in the 18th century by paneled doors, either of solid wood or with fixed lights (panes) to allow light into the entrance way. An overhead transom and sidelights could admit additional light (Figure D). A fanlight is a semicircular window over an entry door, usually with radial muntins. Door surround elements are similar to those seen around windows.

Figure D. Sidelights flank the door on a Greek Revival house.

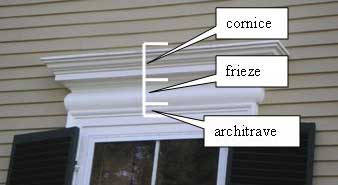

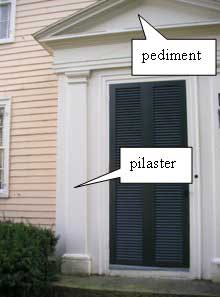

A number of elaborations seen on doors and windows and near the roof-wall junction derive from the Classical orders. An entablature is comprised of a cornice, frieze and architrave. Examples of entablatures are seen in the photographs below on a window and portico (Figures E, F). A pilaster is a flat, engaged column with a base and capital; pilasters frequently flank entrances as part of the surround (Figure G). Pediments, triangular elements deriving from Grecian pediments, are commonly seen over windows, doors and porches (Figure G). Dentils are small, decorative blocks projecting like teeth beneath a cornice (Figure F).

Figure E. Window entablature on a Federal style house.

Figure F. Portico entablature with dentils under the cornice on a Federal style house.

Figure G. Door surround with pilaster and pediment on a Federal house.

Brackets (also called corbels) are supports under horizontal projections like roof eaves, window hoods, and porches (Figure H).

Figure H. Cornice brackets over a bay window on an Italianate style house.

Architectural Periods & Styles

A variety of historic house styles contribute to Andover’s architectural diversity. Admirers of old houses will observe that although some houses are stylistically pure and easy to characterize, many are transitional and exhibit features of several styles and time periods. Like food and fashion, houses were a cultural index of wealth and sophistication, and it was important to “keep up with the Joneses.” Hence the addition of a Federal-era fanlight and shutters to an early Georgian house, or the replacement of 6-pane Greek Revival windows with 2-pane Victorian sash.

New house forms were introduced in urban areas and were often slow to “catch on” in rural areas. House styles that were the height of fashion in Boston or Philadelphia may not have been seen in northeastern Massachusetts and beyond for years or decades. Date ranges provided for each style are generalized timeframes when the houses experienced their greatest popularity in New England.

First Period: 1625–1725

New England’s first colonists built houses that were adaptations of English domestic buildings. Generally one room deep and two stories high with single large, central chimneys, they had steeply pitched roofs and were clad in unpainted wood clapboards or shingles. Sometimes they featured a second story overhang with decorative pendants, as seen in the well-known Paul Revere House in Boston. Because glass was scarce and expensive, window openings were small, few in number, and fixed or casement style with diamond-shaped leaded panes. Doors were batten (constructed of vertical boards).

The Benjamin Abbot House at 9 Andover St. was built in 1685. It has a side gable roof, large central chimney, projecting entrance enclosure, and 12/12 windows.

By the early 1700s, lean-tos were often added to the rear of single unit (one room deep) houses and incorporated under a single main roof to create the familiar saltbox form. Chimneys decreased in size, roof slopes became less steep, and double-hung sash windows with rectangular lights (panes) replaced casement windows. Doors became more elaborate and were surrounded by projecting moldings.

Georgian: 1725–1780

Early Georgian style houses were simple, symmetrical, two-room deep boxes with a side gable, gambrel, or hipped roof. Like First Period houses, they had central chimneys and were sided with wood shingles or clapboards. Windows, always symmetrically spaced, were double-hung with nine or twelve lights (panes) per sash; in New England, the second story windows in most Georgian houses touched the cornice.

Patterned after English models, later examples of the Georgian style were distinguished by Classical details including cornice decorations (usually tooth-like moldings called dentils) and doors capped by decorative crowns or pediments and framed by pilasters (flat columns). Doors were paneled and often featured a row of lights (small window panes) at the top of the door, or above the door in a transom. After 1750, the central chimney was replaced with two end chimneys, and dormers, quoins, and balustrades became more common.

Federal: 1780–1830

Federal (or Federalist) style houses show more refinement than the “chunky” boxes of the preceding Georgian period. They are side-gabled in form with a gable or hip roof, like Georgian buildings, but with a lower pitched roof and side chimneys rather than a single central chimney. Door surrounds may be elaborate, and include sidelights and transoms or elliptical fanlights. Entry porches or porticoes, rarely seen on Georgian houses, are common on Federal houses. Supported by columns, they can be rectangular or circular.

This house on Main Street illustrates numerous defining features of the Federal style, including a columned, hip-roofed entrance portico; a door surround with sidelights and an elliptical fanlight; and a Palladian window above the entry.

Larger panes of glass became more available and affordable after the American Revolution, so Federal houses have larger windows and windowpanes than earlier styles. Windows are commonly 6/6 (six over six, or six panes per sash) with deep, narrow muntins. Window trim is simple, or may consist of a decorative crown or entablature. Three-part Palladian windows appear for the first time in Federal houses on the second story over the entrance.

Roof cornices are often emphasized with decorative moldings, most often with dentils. On high style Federal houses, balustrades can be seen on porticoes or at the roofline. Blinds (shutters) were introduced in the early 19th century along with white paint, which until about 1810 was prohibitively expensive.

A Palladian window surmounts the curved portico with balustrade on this Federal house on School Street.

Greek Revival: 1830–1860

The Greek Revival style was based on the architecture of classic Greek temples and grew from an increasing interest in classical buildings in western Europe and America. It was known as the “National Style” in America between 1830 and 1850 because of its nationwide predominance and popularity. Massachusetts architect-carpenter Benjamin Asher (1773–1845) is credited with disseminating the Greek Revival style through his influential house plan books.

The characteristic element shared by virtually all Greek Revival buildings is the wide band of trim below the cornice, representing the classical entablature. Other defining features include pilasters or paneled trim at the building corners, flat-roofed entry porches supported by round or square columns, and door surrounds that include a transom and sidelights. The sidelights on Greek Revival houses are characteristically nearly door-height versus the partial-height sidelights seen on Federal houses. Windows typically have 6/6 sash with decorative, often pedimented, crowns. Corner squares are often seen on window surrounds. Palladian windows are absent on Greek Revival buildings.

This house on Summer Street shows a characteristic Greek Revival entablature (wide band of trim) under the cornice, full door-height sidelights flanking the entrance, and window crowns.

The windows on this Greek Revival house on Washington Street have corner squares. The enclosed entrance has full-height sidelights and a flat roof entablature.

Paneled window surrounds with pedimented crowns and paneled corner boards are seen on this Greek Revival house on Central Street.

The most enduring innovation of the Greek Revival period was the introduction of the front-gabled house, in which the gable end is turned 90 degrees to face the street. Elaborate examples feature a full-height, full-width colonnaded porch that presents a temple-like façade. In Andover, this high style presentation is seen more often in churches than houses. White body paint and dark green shutters comprised the typical original color scheme for clapboard houses in the Greek Revival style.

The door surround of this front-gable Greek Revival house on South Main Street has a transom and sidelights. The decorative corner boards end at the roof cornice returns.

Picturesque Styles: Gothic Revival and Italianate

Until the middle of the 19th century in America, a single architectural style prevailed at any given time. Georgian, Federal, and Greek Revival styles succeeded each other, each dominating the scene until supplanted by a successor. By the 1840s, a new trend of competing architectural styles emerged in England that would characterize the Victorian era both there and in America. These house fashions drew from the Picturesque, or romantic, literary movement and were inspired by medieval and non-classical themes, rather than the classical themes that defined earlier American architectural styles.

The Picturesque styles are characterized by informality and by intricate, fanciful wood details made possible by advanced manufacturing techniques and mass production. Window sash have one-or two- pane glazing (versus the multiple, small panes of earlier periods), reflecting progress in glassmaking technology. Landscape designer and architect Andrew Jackson Downing popularized the Gothic Revival and Italianate styles with his successful house pattern books, Cottage Residences and The Architecture of Country Houses.

Gothic Revival (1840–1880)

The Gothic Revival style was less popular nationally than the competing Greek Revival and Italianate styles. Used primarily for churches, colleges, and rural houses, it is seen in only a handful of examples in Andover. Steeply pitched roofs, cross gables, and lacy vergeboards (gable trim, also called bargeboards) are the signatures of Gothic Revival houses. The most common plan is symmetrical with a central cross gable and a one-story porch. Typical features include hood molds over pointed arched or rectangular windows and doors, towers, and bay windows.

Andover’s best recognized Gothic Revival house is the John Dove House at 276 No. Main St., built in 1847 by architect Jacob Chickering. Later purchased by William Wood, founder of the American Woolen Mills, it is now known as Arden.

The J.T. Abbot House (1845) at 34 Essex St. was also designed by architect Jacob Chickering. It features an ornate vergeboard at the roof cornice, an arched window in the gable, and castellated trim over the bay window and porch.

Italianate (1850–1885)

The Italianate style was loosely based on rural Italian farmhouses with their characteristic square towers. Sometimes called the “Bracketed Style,” its most obvious distinguishing feature is the use of widely spaced ornamental brackets, single or in pairs, supporting the cornice eaves. Almost always two or three stories in height, Italianate houses have low-pitched roofs with wide, overhanging eaves. Windows are generally tall, narrow, and curved or arched with elaborate crowns; paired and triple windows are common. Doors are often double with heavy molding. Italianate was the most popular house style in America in the 1860s and 70s.

The high style Italianate house at 65 Central Street was built in 1874. The side elevation seen here shows bracketed eaves, double and triple arched windows, and intricate porch balustrades with finials.

Detail of cornice brackets on the Italianate house at 65 Central Street.

The 1846 Benjamin Punchard House at 8 High Street, now owned by Enterprise Bank, shows an early incarnation of the Italianate style. This house is contemporary with the two Gothic Revival examples shown above.

Victorian Era Styles

The term “Victorian” commonly refers to the period of Queen Victoria of England’s long reign (1837–1901), an era whose architecture was characterized by increasing elaboration and complexity made possible by advances in industry. The era encompassed a number of architectural styles, including the Gothic Revival and Italianate fashions discussed in the previous section. In America, the styles that are most strongly associated with Victorianism emerged after 1860; these include Second Empire, Stick, Queen Anne, and Shingle styles. Queen Anne and Shingle — the styles that gained acceptance during the final decades of the period — are characterized by asymmetry, complexity, and surface treatment. These are the styles that are most readily associated with “Victorian” in the public consciousness.

Second Empire (1860–1880)

Because it imitated the latest fashion in French buildings during Napoleon III’s Second Empire, this style was considered very modern in its time. There are few examples of the style in Andover, although along with the Italianate style it dominated urban housing between 1860 and 1880. A mansard (or French) roof with projecting dormer windows is the style’s hallmark. The mansard roof, a dual-pitched hipped roof, could exhibit one of five profiles — straight, flared, concave, convex, or S-curved.

This Second Empire house on South Main Street has a flared mansard roof with dormer windows, decorative cornice brackets, a double window over the entry porch, and paired entry doors.

The Second Empire style was used for many public buildings during the administration of General Ulysses S. Grant (1869–77), including Andover’s Memorial Library, built in 1871 as a Civil War memorial. The library lost its mansard roof in a turn-of-the-century Colonial Revival remodeling

The Second Empire style shares many features with the closely related Italianate style, including eaves with paired decorative brackets and paired windows and doors. Molded cornices, wrought iron roof cresting, and multi-color patterned slate roofs are also defining characteristics of the Second Empire. This tall style was popular for remodeling as well as new construction because the boxy roof allowed for a full story of useable space. In 18th century France, propety tax laws exempted attics from taxation, so a mansard roof had the added benefit of providing a tax-free floor.

This mansard roof on Central Street has a convex profile.

Stick (1860–1890)

Inspired by medieval English building traditions, the Stick style provided a transition between the Gothic Revival and Queen Anne styles. Stick style houses have the steeply pitched gable roofs that characterize Gothic Revival houses and the decorative wood surfaces that became emblematic of Queen Anne buildings. Although the style was broadly disseminated in house pattern books of the time, it was not as popular as the Italianate or Second Empire styles. The Stick style reached its height of expression in Richard Morris Hunt’s houses in Newport, Rhode Island, in the 1870s.

The Stick style is identified by steep gable roofs with cross gables; decorative wood trusses in the gable apexes; overhanging eaves; and patterns of horizontal, vertical and diagonal boards (stickwork) applied to the wall surface. The decorative stickwork, the feature that defines the Stick style, imitates the visible framework seen in half-timbered medieval structures. Stick style buildings are asymmetrical and often feature a large veranda or covered porch, and a square or rectangular tower. Windows are universally rectangular, versus the arched window forms seen in earlier styles. Multi-colored paint schemes were often applied to Stick style houses; the use of complex color palettes was encouraged by the increasingly availability of ready-made paints after the Civil War.

This fine example of the Stick style, built in the late 1880s on Elm Street, exhibits complex stickwork and a characteristic polychromatic paint scheme. The front and cross gables support decorative trusses.

This simple truss adorns an entry porch near the Elm Street example shown above.

Queen Anne (1880–1910)

“Queen Anne architecture” is a misnomer because the style drew no inspiration from the formal Renaissance architecture that dominated Queen Anne of England’s reign (1792–1714). It was named and popularized by a group of English architects who borrowed the visual vocabulary of late medieval styles, including half timbering and patterned surfaces. The William Watts Sherman house in Newport, Rhode Island, built by Boston architect Henry Hobson Richardson and featuring a half-timbered second story, is recognized as the first Queen Anne style house built in America. The British government introduced Queen Anne to America with several buildings it constructed for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, and helped to launch a style that soon replaced Second Empire as the country’s most popular and fashionable domestic architecture style.

This Queen Anne style house on Barnard Street has a complex cross-gabled form with an overhanging roof gable, prominent bay window and decorated chimney.

High-style Queen Anne houses are the most exuberantly decorated and ornate manifestations of Victorian-era architecture. The style’s defining characteristics include an asymmetrical façade; a partial or full-width one-story porch that frequently wraps around one or both sides; a steeply pitched, irregularly-shaped gable roof; elaborate chimneys; towers, turrets and other wall projections (bays and overhangs); and multiple surface materials creating textured walls. Windows generally have simple surrounds and single-paned sash. Entrance doors are single and often feature carved detailing and a pane of glass in the upper half. Stained glass accents are trademark features in doors and windows. Polychromatic paint schemes that emphasize complex trim details are particularly well suited to Queen Anne houses.

This Queen Anne style house has a characteristic wraparound porch.

Four main subcategories of the Queen Anne style have been defined based on detailing — Spindlework (with delicate spindle ornamentation), Free Classic (with classical columns), Half-timbered (with half-timbering on gables or upper story walls), and Patterned Masonry (with patterned brick, stone and terra cotta).

This front-gabled Queen Anne house features spindlework on the porch and patterned shingles in the gable and horizontal trim band. The paint scheme is polychromatic.

Shingle (1880–1900)

Shingle style houses exhibit the irregular building forms and projections of Queen Anne structures, but not their extravagant and fanciful ornamentation. The distinguishing feature that gives the style its name is the use of continuous, naturally weathered shingles on the roof and walls to create patterns of light and shadow. The shingles run uninterrupted around corners and projections, and sweep down roofs and dormers, to create an enclosed, unified shape and color; towers are often blended into the house form rather than defined. Simpler and more elegant than Queen Anne, the style has a distinctly modern character that explains its popularity in contemporary architecture today.

This Shingle style house on Central Street was originally a uniform shade of brown. It features a tower blended into the main body of the house and characteristic curved surfaces in the eyebrow dormer and front gable projection over the paired windows.

In A Field Guide to American Houses, authors Virginia and Lee McAlester describe the Shingle style as a blend of three traditions — Queen Anne (asymmetry, wide porches, shingled surfaces), Colonial Revival (gambrel roofs, lean-to additions, classical columns, Palladian windows) and Richardsonian Romanesque (sculpted shapes, arches). Porch supports are simple, slender wood posts or wide piers of shingle or stone. Windows typically have single-pane lower sash and multi-pane upper sash; multi-light casement windows and multiple window configurations are common.

The first story of this Shingle style building on North Main Street is constructed of field stone. The shingled surfaces curving into the recessed dormer windows are typical of the style.

The Shingle style was introduced in the northeastern United States and reached its zenith of expression in New England in seaside resorts and country estates. It was a high-fashion style favored by architects that, unlike the Queen Anne style, was not widely adopted for use in mass housing.

Colonial Revival (1880–1955)

The Colonial Revival period in America saw a resurgence of patriotism and a return to the styles of the founding fathers. Both a cultural movement and an architectural style, the Colonial Revival was born at the national Centennial Exhibition in 1876. It captured and glorified the past, celebrating 18th century American culture and patriotic values — freedom, democracy, industry, and moral superiority. The influence of the movement was felt in architecture, furniture and interior decoration, landscape and garden design, and the fine arts. Between the World Wars, the Colonial Revival style was the most popular house style in America.

Colonial Williamsburg is a product of the Colonial Revival movement and the preservation fever that swept the country in the 1920s. Interestingly, one of Williamsburg’s first restoration architects, William Graves Perry, lived in Andover (but not in a Colonial Revival style house!). Wallace Nutting, best known for his tinted photographs of recreated colonial scenes and his highly authentic reproduction furniture, was another Massachusetts native in the vanguard of the Colonial Revival movement.

The Colonial Revival style combined architectural elements of the Georgian and Federal periods. The earliest examples were free interpretations of Colonial structures that often featured exaggerated components and awkward proportions. Beginning in the early 1900s, these romanticized interpretations were replaced by carefully researched replicas with correct details and balanced proportions. The more authentic colonial forms were popularized by the White Pine Series of Architectural Monographs, brochures featuring antique houses built of white pine published by the Weyerhaeuser Lumber Company from 1915 to 1940. Georgian Revival is a subtype of the style based on exclusively 18th century characteristics. Other style subtypes and variants include Four Square, Dutch Colonial (Figure D), and Cape Cod.

Figure A. This hip-roofed house on Central Street, built in 1884, may be Andover’s earliest example of the Colonial Revival style. It features corner quoins, a columned portico with a roof balustrade, dentils at the cornice, and three dormers.

Typical Colonial Revival buildings are rectangular, symmetrical structures with gable or hip roofs and dormers. Front doors are usually elaborated with a combination of pediment, pilasters, columns, fanlights or sidelights; windows are double hung and multi-pane, usually with six lights per sash. Palladian windows, broken pediments, and corner quoins are often seen as decorative accents. Cornices are embellished with dentils or modillions.

Despite that fact that the Georgian and early Federal houses that inspired the Colonial Revival style were painted in earth tones and mid-range colors, the Revival’s palette of choice for wood houses derived from the Greek Revival period (1830–1860) — white siding with dark green or black trim. The white houses, both old and new, that dominate the New England landscape today are primarily a 20th century phenomenon. Starting in the 1920s, masonry was progressively more common in Colonial Revival domestic architecture, as seen in the striking collection of brick houses in Andover’s Shawsheen Village (Figures B and C).

Figure B. The door on this pedimented entry is surmounted by a fanlight and flanked by paired engaged columns. The first floor windows are six lights over nine.

Figure C. This house features a circular portico with balustrade, sidelights and a fanlight surrounding the door, keystoned window lintels, and a roof pediment with oculus (circular) window.

Figure D. This prototypical Dutch Colonial in Shawsheen Village is defined by its steeply pitched gambrel roof and shed dormer.

Convincing Colonial Revival houses are sometimes difficult to distinguish from original period houses. Clues that a house is Colonial Revival include bay, paired or triple windows; windows with a multi-pane upper sash over a single-pane lower sash; one-story wings; and numerous or exaggerated broken pediments.

Figure E. The triple windows, fanciful Palladian windows, recessed windows over the entry porch, and compressed broken pediment over the central dormer are clues that this is a Colonial Revival house. It was built on Abbot Street around the turn of the century.

Eclectic and Modern Styles

The Eclectic movement began near the end of the 19th century and embraced a variety of Old World architectural traditions. Emphasizing careful copies of historic patterns, it spawned a number of period revival styles that coexisted in friendly competition — including Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, Neoclassical, Italian Renaissance, and Mission. The Colonial Revival and Tudor Revival styles are well represented in Andover.

Modernism arrived at the turn of the century with its Prairie and Craftsman styles. For a time, these truly American styles interrupted the Eclectic movement's copybook, revival styles. However, after World War I, residential architectural fashion returned to the comfortable period revival styles and remained there until the second wave of modernism appeared in the mid-1930s.

Tudor Revival 1910–1940

The Tudor, or Tudor Revival, style in America was based loosely on medieval English architecture. Enormously popular in the 1920s and 30s, it benefited from advances in masonry veneering technique that allowed for the recreation of English brick and stucco façades. Some of Andover's best examples of the Tudor Revival style are seen in the planned neighborhood of Shawsheen Village, where they share space with Colonial Revival style houses.

Steeply pitched roofs, prominent cross gables, half-timbering, large chimneys with chimney pots, and tall narrow windows with multi-pane glazing are the hallmarks of the Tudor Revival style. Entrance doorways, typically arched, are often elaborated with brick surrounds mimicking quoins. Multi-pane casement windows in groups of three or more are common.

A Tudor Revival house in Shawsheen Village features an arched entrance door, half-timbering on the cross gable, and a large chimney patterned with brick and stone.

Clad in shingles with a steep cross gabled entrance, this Tudor Revival house on Florence Street has a “storybook” feel.

Prairie (1900–20)

The Prairie style was a short-lived modernistic style developed by a group of Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired Chicago architects. Its single most distinguishing characteristic is a shallow hipped roof with widely overhanging eaves, providing a “low to the ground” feel. Prairie houses often feature massive, square porch supports; prominent horizontal elements; and grouped casement windows. They are frequently executed in stucco.

This rare example of the Prairie style in Andover blends beautifully into its natural setting.

Craftsman (1905–1930)

The Craftsman style was born in California and drew inspiration from the Arts and Crafts movement and its focus on natural materials. Widely disseminated through pattern books and magazines, it became the most prevalent style for small houses in the nation until the Depression. One and 1½ story Craftsman style houses are popularly known as bungalows.

In common with the Prairie style, the hallmark of a Craftsman house is its roof. In this case it's generally a shallow gable (versus hipped) roof with overhanging eaves and visible roof beams and rafters. Full or partial-width porches with tapered square supports, often of stone or concrete block, are typical. Characteristic bungalow windows are double-hung with rectangular divided lights in the top sash and a single light in the bottom sash.

This 1½ story bungalow on Walnut Street exhibits many features of a Craftsman style house, including wide eaves, visible roof rafters, a partial porch with tapered columns, and six over one windows.

International, Modernistic, Modern and Neoeclectic (1920–Present)

The International and Modernistic styles; emphasizing horizontals, flat roofs, smooth wall surfaces, and large window expanses; renounced historic precedent in a radical departure from the revival styles. Only a handful of houses represent these styles in Andover.

Most suburban houses built since 1935 fall into the Modern style category. These include the familiar forms we call Cape (officially termed minimal traditional), ranch, split-level and contemporary. The one-story ranch house form, designed by a pair of California architects, was the prevailing style during the 1950s and '60s. Contemporary was the favored style for architect-built houses between 1950 and 1970.

This asymmetric Neo-Victorian house on Salem Street features Queen Anne detailing including its, tower, bays, and porch columns and trim.

Neoeclecticism, which emerged in the mid-1960s and supplanted the Modern style, represented a return to traditional architectural styles and forms. It includes Mansard, Neocolonial, Neo-French, Neo-Tudor, Neo-Mediterranean, Neoclassical Revival, and Neo-Victorian. These styles borrow prominent details from historic models in bold, free interpretations.